What is Antenna Gain in Satellite Communications? (Explained simply)

In satellite communications, RF terminology can quickly become opaque for non-specialists. Concepts such as gain, polarization or axial ratio are frequently mentioned in specifications, datasheets or technical discussions, but they are not always clearly explained outside of purely engineering contexts.

This article is part of Anywaves’ Antenna Encyclopaedia, a series of high-level, educational articles aimed at demystifying key RF and antenna concepts used in space missions. The goal is not to dive into complex equations or antenna design theory, but to provide clear, accurate and useful explanations for system engineers, project managers and space professionals who interact with RF topics without necessarily being antenna specialists.

In previous articles of this series, we have already covered concepts such as:

- Axial ratio and its role in space antenna performance

- The differences between EM, QM and FM antennas in the space development cycle

- Signal polarization and why it matters for space links

- The distinction between RHCP and LHCP antennas

- Active versus passive space antennas, and how to choose between them

In this article, we focus on another fundamental concept that appears in almost every satellite antenna datasheet and link budget: antenna gain.

What does “antenna gain” actually mean?

At a very high level, antenna gain describes how effectively an antenna concentrates radio energy in a particular direction.

If you’ve ever heard someone say “we need a higher-gain antenna”, it can sound like a request for more power. In reality, antenna gain is not extra power. It is a way of describing how the antenna redistributes the RF energy it is given.

A useful mental image is the following:

- A low-gain antenna behaves like a lamp: it illuminates a wide area, but not very far.

- A high-gain antenna behaves like a flashlight: it reaches farther, but over a narrower area.

The antenna does not generate energy. It simply concentrates more energy in some directions and less in others.

This directional concentration is what we call gain.

More formally, antenna gain tells you how much stronger the signal is in the antenna’s best direction compared to a reference radiator.

Antenna gain is directional — not “extra power”

Two important clarifications are essential to properly understand antenna gain.

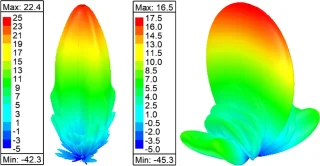

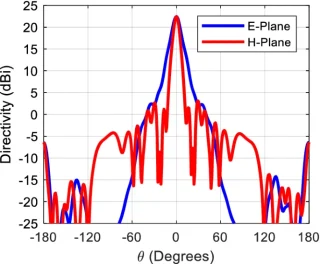

Example of a directive antenna.

Gain is directional

Antenna gain is not a single, uniform boost. It depends on the observation angle around the antenna:

- it reaches a maximum in the main radiation direction,

- it decreases away from that direction,

- it can be very low (or intentionally suppressed) in others.

In satellite communications, this matters because the communication link only exists in specific directions (toward Earth, toward a relay satellite, or toward a ground station during a pass).

Gain includes losses

In antenna theory, gain is often described as:

Gain = Directivity × Efficiency

In simple terms:

- Directivity describes how narrowly the antenna focuses energy.

- Efficiency accounts for losses due to materials, mismatch, heat dissipation, and manufacturing effects.

This explains why two antennas with similar radiation shapes can still have different gains if one is less efficient than the other.

Types of antenna gain: dBi and dBd

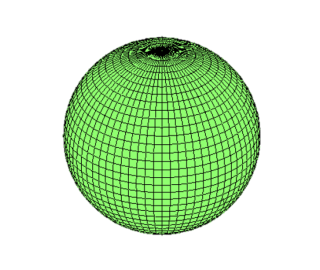

Illustration of an isotropic radiator.

Antenna gain is always expressed relative to a reference, and the reference matters.

Isotropic gain (dBi)

dBi means decibels relative to an isotropic radiator.

An isotropic radiator is a purely theoretical antenna that radiates energy equally in all directions. It does not exist physically, but it provides a clean and universal reference.

Because of this, dBi is the standard unit used in satellite communications and space link budgets.

Dipole gain (dBd)

dBd means decibels relative to a half-wave dipole antenna.

It is more commonly encountered in terrestrial RF applications. The relationship between the two is fixed:

dBi ≈ dBd + 2.15 dB

Why this matters

When reading antenna datasheets or specifications, always check: gain relative to what?

A number expressed simply in “dB” without a reference is ambiguous and can easily be misinterpreted.

What is an antenna coverage (radiation) pattern?

Antenna gain cannot be understood without looking at the coverage pattern, also known as the radiation pattern.

The coverage pattern is a representation of how RF energy is distributed in space around the antenna. It shows:

- where the antenna radiates strongly,

- where it radiates weakly,

- and how energy varies with direction.

- Example of a 3D Radiation Pattern

- Example of a 2D Radiation Pattern

Radiation patterns are often shown as:

- 2D polar or rectangular plots, or

- 3D representations, sometimes overlaid on the desired coverage area using modern radio-planning or mission-analysis tools.

In satellite missions, the radiation pattern is often just as important as the peak gain value itself.

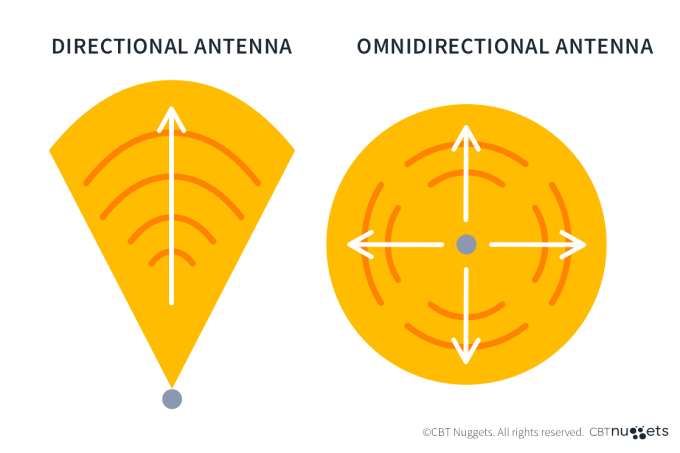

Omnidirectional vs directional coverage patterns

Omni VS Directional antenna. Credit: CBT Nuggets.

Omnidirectional antennas

Omnidirectional Radiation

An omnidirectional antenna radiates approximately equally in all horizontal directions. These antennas are typically used when 360-degree coverage is required.

In practice, gain in omnidirectional antennas is often achieved by narrowing the vertical beamwidth, rather than by focusing energy azimuthally.

Such patterns are useful for:

- spacecraft with limited pointing knowledge,

- safe-mode or contingency communications,

- applications requiring high robustness across attitudes.

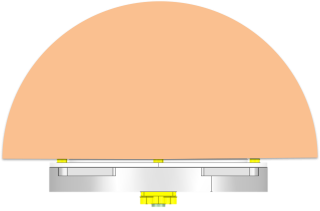

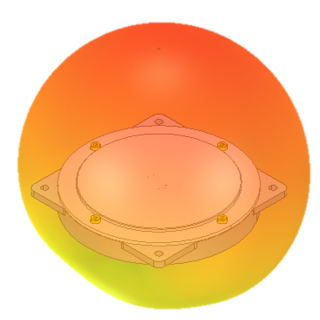

Directional antennas

- Radiation focused into a dedicated direction, here the upper half-space.

- Hemispherical Radiation

A directional antenna concentrates energy in a specific direction.

These patterns are used when:

- communicating with a known target,

- maximizing link margin,

- reducing interference and noise from unwanted directions.

Directional antennas are common in:

- point-to-point links,

- high-data-rate satellite communications,

- radar and remote sensing systems.

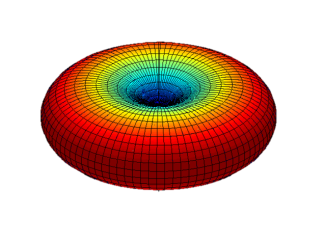

The relationship between antenna gain and coverage pattern

Antenna gain and coverage pattern are fundamentally linked by the principle of energy conservation.

- When gain increases, energy is focused into a narrower beam, producing a more directional pattern.

- When gain decreases, energy is spread over a wider area, producing broader or omnidirectional coverage.

This leads to a key trade-off:

Higher gain → narrower coverage (smaller beamwidth)

Lower gain → wider coverage (larger beamwidth)

Illustration of the Maximum Gain

Beamwidth, expressed in degrees, is therefore inversely related to antenna gain.

Why this trade-off matters at spacecraft level

Satellite links are hard because the signal travels very far through free space. Even for LEO, the path loss is significant, and for higher data-rate missions it often becomes a central driver. A narrow beam can be very effective — if it can be pointed correctly. But it also increases system-level complexity.

Higher-gain antennas may require:

- more accurate attitude determination and control (ADCS),

- tighter pointing budgets,

- careful operational planning (tracking, handovers, pass geometry).

As gain increases, small pointing errors can lead to significant link degradation. This is why antenna gain decisions are never purely RF decisions — they are spacecraft and mission architecture decisions.

Common misconceptions about antenna gain

“Higher gain means more transmitted power”

No. The transmitted power is set by the radio. Gain only changes how that power is spatially distributed, meaning how the antenna redistributes that power – less in some directions, more in others.

“Higher gain is always better”

Not necessarily. Many missions intentionally favor moderate or low gain to ensure:

- wide angular coverage,

- robust TT&C links,

- communication capability during safe mode or tumbling phases.

Sometimes moderate gain + wide beam is the right engineering choice.

“Antenna gain is a single number”

Datasheets often show peak gain, but in practice engineers care about:

- gain over the useful coverage region,

- off-axis performance,

- integration effects with the spacecraft structure.

A quick “when to choose what” guide

Here is a simple, non-controversial way to think about it:

Lower / moderate gain tends to fit when…

- You want broad coverage

- You need comms robustness across many attitudes (or safe mode)

- The link is low to moderate data rate and margin is acceptable

Higher gain tends to fit when…

- You need higher data rates or longer links with limited power

- You have good pointing capability

- You can accept narrower coverage and operational constraints

This is intentionally simplified – but it matches how many teams think in early trade-offs before diving into detailed RF simulations. These trade-offs are usually refined later using detailed link budgets and radiation pattern analyses.

Antenna gain: the key takeaway

Antenna gain is a measure of how effectively an antenna concentrates RF energy in a given direction, usually expressed in dBi. Increasing gain improves signal strength in that direction, but almost always reduces coverage – making gain a system-level trade-off rather than a simple performance metric.

Frequently asked questions about antenna gain

Is antenna gain the same as amplification?

No. Antenna gain does not create additional power. It describes how the antenna focuses the available RF energy in certain directions. The transmitter output power remains the same; the antenna redistributes it spatially.

What is a “good” antenna gain for a satellite?

There is no universal “good” value. The right gain depends on:

- required coverage

- pointing accuracy

- data rate

- mission phase (nominal vs safe mode)

In many missions, moderate gain is intentionally chosen to ensure robust communication over a wide range of attitudes.

Why do high-gain antennas have narrow beams?

Because focusing energy into a smaller angular region increases signal strength in that direction. This is a fundamental physical trade-off: energy concentrated more tightly cannot cover as wide an area.

Does antenna gain depend on frequency?

Yes, indirectly. At higher frequencies (shorter wavelengths), it is generally easier to achieve higher gain with a physically smaller antenna. This is one reason why higher-frequency bands are often used for high-data-rate links.

Why is antenna gain often quoted as “peak gain”?

Datasheets typically show the maximum gain of the antenna. In practice, engineers also care about gain over coverage, off-axis behavior, and how the antenna performs once integrated on the spacecraft.

Contact

us

If you have any question, we would be happy to help you out.