Other news

What Makes a Good Space Engineer Today? Skills, Mindset, and the NewSpace Context

Read more

What is Antenna Gain in Satellite Communications? (Explained simply)

Read more

Space reviews aren’t ceremony; they’re how we keep cost, risk, and schedule under control.

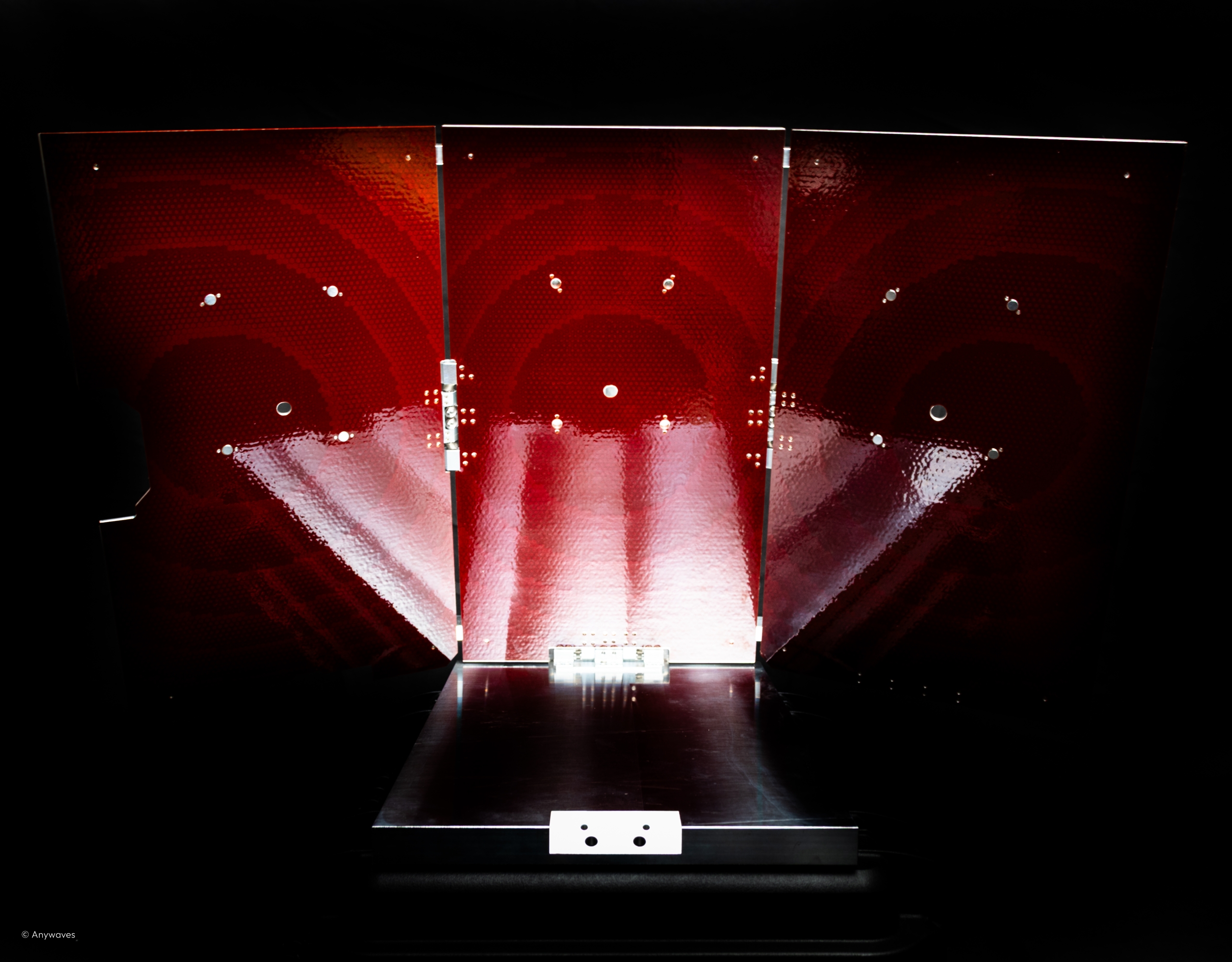

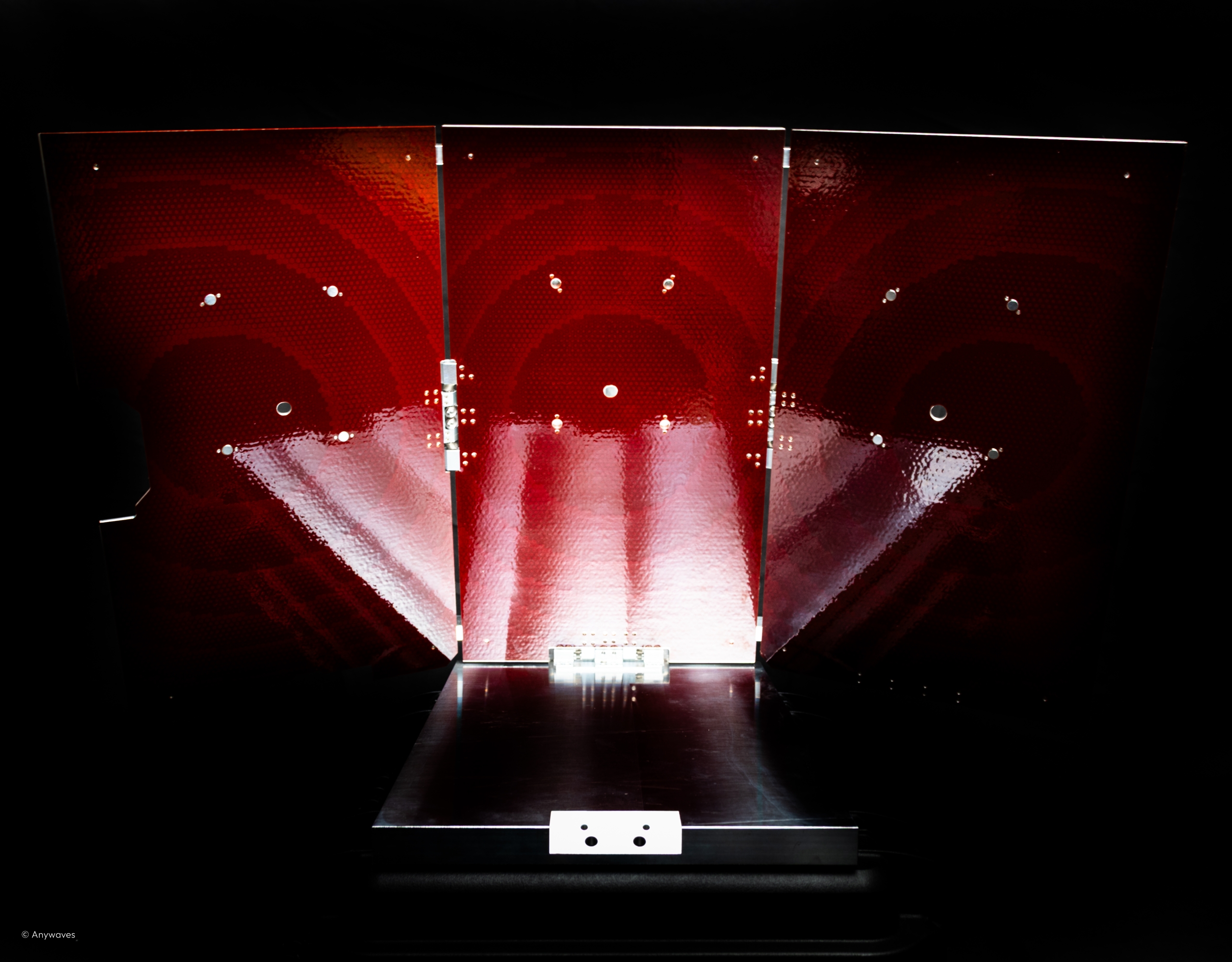

At Anywaves, we build and qualify flight antennas and RF subsystems for primes and integrators. Across cubesats, constellations, and agency missions, the same pattern works: SRR → PDR → CDR → MRR → TRR → QR → FRR/LRR → ORR → Acceptance.

Each gate answers a simple question: are we ready to move to the next irreversible step with the right evidence?

In this guide, we’ll keep definitions short, expectations concrete, and advice practical. We hope you’ll find this article useful!

Need the high-level flow before diving into details? This snapshot gives you the sequence and what each gate authorizes. Treat it like a checklist preview; the next sections unpack the why and the how.

What are the standard milestones in a space hardware project?

Most programs follow this gated sequence:

SRR (System Requirements Review) → PDR (Preliminary Design Review) → CDR (Critical Design Review) → MRR (Manufacturing Readiness Review) → TRR (Test Readiness Review) → QR/TRB (Qualification Review/Test Review Board) → FRR/LRR (Flight/Launch Readiness) → ORR (Operational Readiness) → Acceptance & Delivery.

Each gate freezes key decisions and authorizes the next phase – design, build, test, flight, or operations.

With the sequence in mind, let’s look at why these reviews exist in the first place, and why skipping or weakening one usually costs more than it saves.

Space projects commit irreversible cost at design freeze, long-lead procurement, integration and test, and launch. Reviews are formal risk gates: they have entry criteria, auditable evidence, and exit criteria. Pass the gate, and you’re authorized to spend more risk capital (time, budget, and schedule slack). Fail it, and you avoid much costlier rework later.

Naming varies by agency and prime. This guide uses widely understood labels (NASA/ECSS/common industry) and keeps the intent constant: prove feasibility early, freeze interfaces on time, qualify the design before flight, and fly safely.

Space program reviews follow shared intent but not identical checklists. Primes (main contractors) usually own FRR/LRR and the launch campaign boards. Specialist subcontractors like Anywaves focus on design/industrialization, qualification, production, and delivery, and typically participate in customer-led FRR/LRR without chairing them.

How we usually sequence it at Anywaves (subsystem supplier):

SRR → PDR → CDR → MRR → TRR → TRB (Qualification Review) → Operational Review (with the customer) → Industrialization review → FAI (first article for series) → Production/ATP → Acceptance & Delivery (EIDP + CoC).

So, while you may see FRR/LRR on prime-owned programs, our owned gates after qualification are Operational/Industrialization reviews, FAI, then production and acceptance. This is normal tailoring for subsystem suppliers on agency and commercial missions.

Each review answers one simple question: “Are we ready to spend the next tranche of budget and schedule without creating avoidable rework?” The bullets under every gate are the minimums you should expect to put on the table if you want a clean pass.

Confirms requirements are complete, consistent, and verifiable, with a clear verification plan. Establishes initial budgets (mass, power, RF, thermal) and constraints.

Once requirements are truly testable, the next challenge is turning them into a design with margin that real hardware can implement.

Validates the baseline architecture and interfaces with credible margins. Authorizes detailed design work and planning for long-lead items.

With the baseline accepted, it’s time to remove ambiguity. CDR asks for the details that manufacturing and test will rely on.

Demonstrates the detailed design is complete, producible, and traceable to requirements. Freezes drawings/BoM/ICD and releases the build and test hardware.

A frozen design only matters if the factory can build it repeatedly and safely. That’s exactly what MRR validates.

Shows processes, tooling/fixtures, routings, and special processes are controlled and ready. Green-lights fabrication under defined quality controls.

With manufacturing prepared, testing becomes the next source of risk. TRR ensures you are about to run the right tests the right way.

TRR is permission to press “Start.” Procedures, setups, instruments, facilities, and safety must be right before you expose hardware to qualification levels.

Executing tests is necessary; interpreting them correctly is decisive. QR/TRB turns raw data into a formal declaration of design fitness.

QR/TRB is where you prove the design survived worst-case environments and still meets performance. Close the NCRs, justify deltas, and lock the qualified baseline.

With the design qualified, attention shifts from “can it survive?” to “are we ready to fly it safely and on time?”

FRR/LRR integrates people, procedures, hardware, and logistics. It’s the final check that nothing stands between you and the launch campaign.

Launch isn’t the finish line; it’s the handoff to operations. ORR prepares the ground segment and the team for day-one realism.

ORR confirms that commissioning plans, fault responses, and ground systems are ready – so first contact and early maneuvers look routine, not improvised.

Operations can’t start without clean acceptance. The last gate is administrative on paper, but critical in practice.

Formal customer acceptance of the flight article(s) based on the EIDP and Certificate of Conformity. Confirms configuration, traceability, and ATP results.

Acceptance turns a flight article into a delivered product. Clear traceability – what was built, how it was tested, and why it conforms -prevents disputes and delays.

PDR vs. CDR—what’s the difference?

A: PDR freezes the baseline design and interfaces; CDR freezes the detailed design (drawings/BOM/tolerances) and authorizes manufacturing.

What is MRR?

A: Manufacturing Readiness Review confirms processes, tooling, routings, and special processes are ready and controlled, so production can start without introducing new risk.

TRR vs. QR—how do they differ?

A: TRR authorizes running the tests; QR (via a TRB) reviews results to declare the design qualified.

FRR vs. LRR—how do they differ?

A: FRR checks overall flight readiness; LRR confirms the team, hardware, and logistics are ready to enter the launch campaign.

What documents unlock acceptance/delivery?

A: An EIDP (as-built, test reports, calibration) plus a Certificate of Conformity—these allow the customer to formally accept the hardware.

From our side of the table, programs run smoothly when teams do five things well:

Do this, and reviews feel routine, not stressful. Schedules hold, integration stays predictable, and commissioning starts faster.

If you need a flight-proven RF subsystem partner who can plug into your gated lifecycle, manage interfaces with discipline, and deliver clean qualification/acceptance evidence, we’re happy to align with your standards and cadence!

If you have any question, we would be happy to help you out.